Is there anything that provides a grimmer testament to human frailty than the Abu Ghraib pictures now available on the web? When you see these pictures, many react with disgust, anger, horror, or perhaps pity. Maybe you even react dumbly and uncomprehendingly. After all, they are pictures of men stripped naked and put into positions that make no sense. You have to think the brute reality of their physical discomfort into the pictures. The pictures themselves don't breathe the sighs or the smell of bodies contorted into shapes and positions meant to humiliate and demean. Pictures don't bleed.

But there's more to a picture than what's seen. That we fill that unseen void with our own nightmares or lack of feeling or overblown sense of pity--is it there where the gulf between human and human eventually erupts and discharges its foul poisons? For no picture can grasp that image that eludes every camera, that sense of who we are and that no word will ever inscribe on paper or sand but whose carcass can taunt with nagging ignorance.

These pictures tell a mute story of desolation and desecration; the profane shock of nude men that have become nothing but masses of flesh and hooded mannequins. They elicit more of that final and ultimate irony: our safe securities are nothing but lies and self-deception. ...

One thing that the photos from Abu Ghraib do not document and perhaps cannot show is the fragile hold that custom and ritual have on our lives. You have to delve deeply into the literature to see the concerted regime undertaken by the torturers to reduce these men to mere zeroes. The awful truth revealed by this psychological desecration is that what binds us to each other is quite tenuous and that it breaks quite easily in times of crisis and stress.

Humans are indeed a product of their culture and environment. This is a sad truth that the torturers and their medical gurus know well how to exploit and destroy. To break someone down, attack, mock, and crush their most sacred customs and ideals. Isolate, intimidate, deafen with noise to disconstruct a human being into its most elemental parts. And when the human grovels at your feet begging for mercy, start to retrain it and make it compliant and scarred for life. In this condition they might even learn how to kill for you.

Humans can and will mistreat each other much like a bad dog trainer treats an untrained dog. Given the right circumstances and the right conditions, to paraphrase Simone Weil, humans are capable of the most despicable crimes. The problem is, she said, that most of us will not admit that truth to ourselves. Instead, we work under the illusion that we wouldn't do it, we couldn't do it. ...

Our leaders want us to believe that what will save us is something called civilization. The Pope, for example, has joined the choir of those singing the hosannas of western culture and civilization. (Also see 700 Club reporter's comments.) Along with Pres. Bush, the Pope tells us that Christianity itself is threatened by the terrorists. This choir makes common cause on the Scylla and Charydbis of secular relativism and Islamic fundamentalism.

Were we to sacrifice a billion lives on the altar of western culture, would it produce a society where these crimes would never again arise? Given the assumption of original sin shared by the Pope and Bush, they cannot guarantee any such thing. And given the inability of social and cultural constructs to ensure this, why should I care whether western civilization survives or not?

The Pope’s and Bush’s view makes the basis for individual salvation count on belonging to a group of believers; belonging to this group somehow works magically to obviate the consequences of individual evil--that is, just as long as I belong to the group I am saved. Like those terrorists that say their group is the one to belong to, civilization has now come to a war between what group guarantees salvation or not.

Nothing in culture or civilization will save me from having to face the evil over and over that might face me as a possibility. Never, until time itself ends. The trumpet blare to fight for and save civilization as though it means the salvation of myself is just as much a manifestation of nihilism as the nihilism that these politico-religious leaders say they are out to destroy.

Religiously minded nihilism destroys values and guts self meaning as surely and widely as does the nihilism of secularity. Both purvey a type of self-consciousness that means joining the herd. Like any other consumer movements, religious institutions cannot but mirror this process since they have bought into the presuppositions of nihilism itself. And they themselves are part of the problem.

There are millions of ways that religious nihilism accommodates with purely temporal productions a universal human desire for happiness. Not only does the loss of cultural and social roots create the types of nihilism and violence exhibited by various religious fundamentalisms--Islamic, Jewish, Xtian, and Hindu--civilization and the need to ensure its survival also produces various forms of fascistic political regimes that fill the ennui and despair with repressive and nihilistic gestures.

As Kierkegaard noted long ago, modern individuals face a stark choice: join the fundamentalist charge back to the "origins," the culture of mass mind (mirror image of secularism itself) and thereby lose your real self in mindless despair. Or one can choose to realize the temporality of existence and in radical self-choice disengage oneself from the surrounding world; self-consciously aware of one's eternal destiny.

The way of the solitary individual is a narrow gate that few will enter. The modern age is a time when the spiritual is gutted and enervated to the point that even understanding that one has an eternal self is a joke and a scandal. Unless you can regain primitivity your only health will be envy, resentment, and the anger of the mutant lashing out an alien world.

False religion and its call to group identity destroy the true desire for love and community. Merge into the faceless herd of civilizattional religion or respond to the task of becoming a self, an individual of true faith striving to attain a perfection that you know in dreams but that existence itself tells you is impossible.

Related Links

Read more!

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Civilization@Risk

0

comments

Labels:

disgust,

kierkegaard,

religion,

torture,

xtianity

![]()

Facing the Animal In Us

As many people will know, domesticated animals easily adapt to their human owners' way of life. This adaptive behavior is upset, though, when the pet acts in ways that exhibit the genetic predisposition built into them. When a dog, for example, turns from friendly companion to vicious turf defender, owners are not only surprised, they also make numerous excuses that try to cover up the "indecent" behavior exhibited by friendly Fido.

Of course, in my tortured brain these events align with some things I have written about concerning Milgram's experiments into authoritarianism and Wittgenstein's attack on theory. That is, genetic make-up taking over and undermining domesticity of the family dog exhibits strange parallels to how humans act against even their most cherished values in such conditions as authoritarian hierarchies and rationalized societies.

I'll try to describe how I see some of this thinking working itself out. The following comments are obviously hastily written and would require augmentation in many ways.

One of the fall-outs of the Milgram experiments is that people often act against their own ethical and moral principles. That is, even though someone might oppose cruelty to other human beings in theory, when it comes to performing acts commanded by authority figures and as part of some "objectively" structured situation , they often perform acts that contradict what they say are their most cherished beliefs and values.

In his work on sociology and theory, Wittgenstein and the Idea of a Critical Social Theory: A Critique of Giddens, Habermas and Bhaskar, Nigel Pleasants notes that liberal sociologists and liberals in general often reject Milgram's findings because they contradict an assumed theory of human nature that sees human nature as inherently rational and disposed to do good. To over-simplify, Pleasants understands this rejection of Milgram's research as a predilection for theory according to which all things human must coincide.

Pleasants explains that Wittgenstein's approach to philosophical analysis undermines this theoretical bias. Instead of theorizing about human action, Wittgenstein talks about describing things that are so obvious that we simply ignore them, though their power to dispel illusions and "philosophical" questions is overwhelming. One thing that militates against the "simple" explanation is that it's so common and so "Doh." Yet, this very ordinariness, when seen in its interrelatedness with other similarly ordinary things and events takes on a truly awe-inspiring grandeur. In a world with a predilection for spectacle and the sexified, such ordinariness does not captivate enough.

Without going into the full range of Pleasants' and Wittgenstein's arguments, I must admit that I often understand their points intellectually. While I've had some experience with the way that a non-theoretical approach to dispelling self-delusions works, I had some problem with the Milgram experiments. This is not to say that I haven't seen the psychological mechanism described by Milgram at work, but it does mean that I have not drilled down deeply enough into my psychological make-up to see how the mechanism works in my own everyday actions.

What Wittgenstein talks about simply comes in the flow and stream of life. To pull oneself out of it, so to speak, is exactly what thinkers like Wittgenstein, Kierkegaard and Heidegger meant when they discuss the distorted view about reason's role in making decisions. That is, as Heidegger puts it, we only attend to the world in a rational way when things begin to break down. In the course of living life, we simply live it, embedded in its practices and language in a way that makes living possible.

The wish to theorize and impose a theory onto what we actually experience runs very deep, even in those that do not practice philosophy "officially." This common propensity to formulate and impose theoretical models onto reality is something that Wittgenstein's work deals with. While many see his work as just applying to professional theorizers in the sciences--as it surely does--it also applies to people in general. The desire to come up with a theory that explains it all for you, so to speak, is the source, I;d venture, for many phenomena that includes conspiracy theories to ideology.

The idea that humans are genetically related to animals, and monkeys or apes in particular, repels many people it seems. This observation has been exploited by numerous authors recently on several sides of the political spectrum. Some on the Right, for example, see disgust as a natural instinct that should form the basis for what called natural law. Others, on the Left, see many facets of disgust as socially conditioned.

The problem with these theories is that they attempt to explain large swathes of human behavior as only related to disgust. The appeal of an emotion like disgust for politically oriented thinkers is that it is a hidden psychological process that seems to control and define our behavior. The scientist--or politically motivated philosopher--can use this discovery about a hidden mechanism to seemingly explain human nature. The appeal here is obvious: it gives the illusion that I can explain why humans do what they do. It's especially appealing to those who wish to find eternal truths that cannot be overturned by contingencies.

Have we reached bedrock--as Wittgenstein would say--with an emotion like disgust? Is it, instead, a mainly socially conditioned response in an otherwise open human ability to create and sustain a personality over time? The notion of a theory itself is in question here. While it seems true that disgust is a powerful emotion, it seems too much to say that it is eternal in any sense and must or should form the basis fora personal ethical understanding of life. Instead, we might do well to stay at a more profound level whereby we resist intellectualizing the emotion and remaining aware of those times when we experience disgust and reflect on whether the emotion is just or not.

In the same way, though, we should remain receptive to situations wherein others exploit and marshal the emotion to promote unjust "solutions" to events that might best be reflected on and discussed in more rational terms.

At the same time, we must remain vigilant for the animal that sits at the door of our actions and waits to drive us to ravine and fear and compel us to act in a way other than the human.

Read more!

0

comments

Labels:

disgust

![]()

Friday, June 23, 2006

More Nussbaum; This Time on Shame AND Disgust

Fascinated by the intellectual depth and emotional profundity of Nussbaum's work on disgust and shame in the law, I offer the following article she wrote for Chronicle of Higher Education. ...

Summing up why shame and disgust are ambivalent criteria to use in the law, Nussbaum writes: In general, a society based on the idea of equal human dignity must find ways to inhibit stigma and the aggression that are so often linked to the proclamation that "we" are the ones who are "normal." Such a society is difficult to achieve, because incompleteness is frightening, and grandiose fictions are comforting. As a patient of the psychoanalyst Donald W. Winnicott said to him, "The alarming thing about equality is that we are then both children, and the question is, where is father? We know where we are if one of us is the father."

Related Links

Read more!

It may even be that a society in which people acknowledge their equal weakness and interdependence is unachievable because human beings cannot bear to live with the constant awareness of mortality and of their frail animal bodies. Some self-deception may be essential in getting us through a life in which we are soon bound for death, and in which the most essential matters are in fact beyond our control. But if we cannot fully achieve such a society, we can at least look to it as a paradigm (as Plato said of his ideal city), and make sure that our laws are the laws of that community and no other.

0

comments

Labels:

disgust

![]()

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

The Rhetoric and Politics of Disgust

What has struck me about the rhetoric used by the Right is its spitefulness and ugliness. I find it telling that the Right accuses the Left of being angry, as though that were a profane emotion. As several postings at Unclaimed Territory have pointed out, anger is not an unreasonable emotion in many contexts, especially the field of political debate. Yet, the Right has attempted to stigmatize anger as though it is something unreasonable and ultimately unethical. As Martha Nussbaum has pointed out, however, it is anger at injustice and wrong that forms much of the underlying basis for the legal system. ...

I allude to Nussbaum and her recent work on disgust, shame, and the law (Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law) can give some insight into the rhetorical tactics currently used by the Right.

To shorten this comment, I'll simply provide a quote from Nussbaum that I believe explains the emotion that the Right hopes to exploit in its political strategy. This emotion is disgust. Nussbaum quotes conservative bioethicist Leon Kass, who head Pres. Bush's commission that examines the ethical issues surrounding stem-cell research:

According to Kass, there is a "wisdom" in our sentiment of "repugnance," a wisdom that lies beneath all rational argument. When we contemplate certain prospects, we are disgusted "because we intuit and feel, immediately and without argument, the violation of things that we rightfully hold dear." Repugnance "revolts against the excesses of human willfulness, warning us not to transgress what is unspeakably profound." Kass admits that "[r]evulsion is not argument," but he thinks that it gives us access to a level of the personality that is in some ways deeper and more reliable than argument. "In crucial cases...repugnance is the emotional expression of deep wisdom."

Now Nussbaum wants to show that recent legal cases by conservatives have attempted to make disgust a legal criterion. She argues that it's an invalid criterion for various reasons. She also explain how disgust lies at the root of homophobia, anti-Semitism, and violence against women.

Be that as it may, how this relates to Coulter et al, is in how their rhetoric is an expression of disgust. At the same time that it expresses the author's disgust with numerous subjects, it also hopes to elicit in the reader a sense of disgust. The theory behind this rhetoric follows Kass in his belief that disgust is a truer and more authentic basis for morality and ethics (and by extension the law) than rational argument.

If the preceding is true, then we can say that Coulter, Limbaugh, et al hope to forestall rational debate and discussion and evoke what they perceive as moral sentiments that in some way are truer to reality than reason. In this sense, then, it is inaccurate to call Coulter's work an exercise in hate or anger but rather a rhetoric of disgust.

Related Links

Read more!

0

comments

Labels:

disgust

![]()

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Fascism, Aesthetics, Nussbaum, and Disgust

In my draft essay on fascism, I listed several important elements of fascism as I had understood them from my own experience growing up with a fascist father. One aspect of fascism that I missed in my remembrance was that of disgust--at the world, at oneself, at others. ...

In my draft essay on fascism, I listed several important elements of fascism as I had understood them from my own experience growing up with a fascist father. One aspect of fascism that I missed in my remembrance was that of disgust--at the world, at oneself, at others. ...

I recently came across a work by Martha Nussbaum, a philosopher whose work on emotions has to be the most relevant and insightful work by a thinker in America for the last half-century. The book that has piqued my interest the most is her work on disgust, as it related to women's bodies but also more generally as it plays itself out on the wider social scale, especially in the law.

In the introduction to that work, Nussbaum writes:What I am calling for, in effect, is something that I do not expect we shall ever fully achieve: a society that acknowledges its own humanity, and neither hides us from it nor it from us; a society of citizens who admit that they are needy and vulnerable, and who discard the grandiose demands for omnipotence and completeness that have been at the heart of so much human misery, both public and private. To that extent, its spirit is less Millian than Whitmanesque: it constructs a public myth of equal humanity, to substitute for other pernicious myths that have long guided us. Such a society remains elusive because incompleteness is frightening and grandiose fictions are comforting. As a patient of Donald Winnicott's said to him (in an analysis that I shall analyze in detail in chapter 4), "The alarming thing about equality is that we are then both children, and the question is, where is father? We know where we are if one of us is the father."20 It may even be that such a society is unachievable, because human beings cannot bear to live with the constant awareness of mortality and of their frail animal bodies. Some self-deception may be essential in getting us through a life in which we are soon bound for death, and in which the most essential matters are in fact beyond our control. What I am calling for is a society where such self-deceptive fictions do not rule in law and in which--at least in crafting the institutions that shape our common life together--we admit that we are all children and that in many ways we don't control the world.

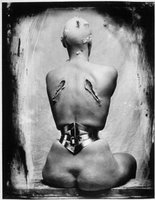

I must admit that disgust has informed some of my own aesthetic works, in terms of eliciting disgust as well as its relationship to the sublime and beautiful. I've always been fascinated by the work of Joel Peter Witkin. His photographic fanstasias play on this juxtaposition of disgust and the sublime--especially in relationship to myth.

Related Links

Read more!

1 comments

Labels:

disgust,

fascism,

fascist

![]()